The now-disappeared city of Siri has a somewhat grim and frightful legend behind it: its name ‘Siri’ is believed to have come from the word ‘Sir’ or head, since the heads of 8000 Mongol invaders were buried in the foundation of this fort. Another legend says the heads of captured Mongol invaders were regularly hung from its walls, leading to its name becoming Siri. Built by Alauddin Khilji during 703 A.H. (1303-04 A.D.) in an area presently occupied by Shahpur Jat, Shaikh Sarai, Hauz Khas, Green Park and Panchsheel Enclave, it was raised to defend against the waves of Mongol invaders. At that time, the three-decade long Khilji dynasty had just been established in 1290. The Saljuq Empire in Western Asia was breaking up, being under constant attack by the Mongols, and Delhi was their next target.

Jalaluddin Khliji: The ‘Mild’ Emperor Who Founded a New Dynasty

After nearly 80 years of rule by the Turkish Slave dynasty, Sultan Jalaluddin Firoz Khilji ascended the throne in 1289. Aware of the pockets of resistance to the change of royal dynasty still existing in Delhi, he made his capital on the outskirts of Delhi at Kilu-ghari (* for Kilu-ghiri , please see side note 1). He made Alauddin, his brother’s son as well as his son-in-law whom he had brought up from infancy, an amir.

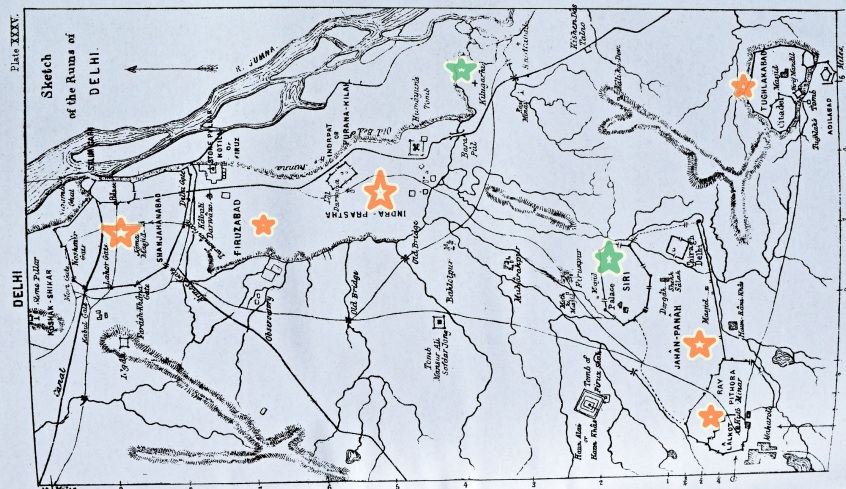

( Green starts showing the cities of Siri and Kilughari, from the map of ‘Ruins of Delhi’, Alexander Cunningham’s Report, Ref 2, plate XXXV, Reproduced with kind permission of Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.)

( Green starts showing the cities of Siri and Kilughari, from the map of ‘Ruins of Delhi’, Alexander Cunningham’s Report, Ref 2, plate XXXV, Reproduced with kind permission of Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.)

However, a nephew of Sultan Balban of the erstwhile Turkish Slave dynasty, Malik Chajju, decided to raid Delhi with a few of his supporters and descendants of Balban. The two armies engaged each other near Badaun, and the new sultan, Jalaluddin, was victorious. The great poet Amir Khusrau was present when the generals of the invading army were brought before the sultan with their hands tied behind them. Jalaluddin, on seeing the sorry state in which the prisoners were brought to him, immediately ordered them to be freed, and treated them with wine and food while consoling them that their action was understandable since they were fighting for their dynasty. Alauddin was entrusted with the governorship of Karra, which was previously held by Malik Chajju, where he came into contact with the generals and noblemen of his predecessor who hinted that, given enough money, Delhi could easily be captured. Alauddin was on bad terms with his wife and his mother-in-law, and started to nurture a dream to capture the kingship sooner or later.

In Delhi, the mildness and clemency of the new sultan was evident in day-to-day affairs. Whenever any thief or mischief-monger was caught and brought to the sultan, he freed them on the condition that they would not repeat their deeds. Everywhere, noblemen started discussing the ineffectiveness of the new sultan, and conspiracies were hatched in secret gatherings on how to eliminate and get rid of him. The sultan was made aware of the plotting, but he always turned a blind eye, saying people tend to talk lightly when drunk. Perhaps, he was quite confident that his good deeds in forgiving people would earn him enough goodwill to tide over the occasional bursts of discontentment.

It is said that bad fortune descended on his kingdom the day he ordered the execution of the famed darwesh, Sidi Maula. He was a disciple of Baba Farid at Ajodhan, and had a large khanqah (convent) where he distributed large quantities of free food every day to the poor and to travellers. In the evenings, many noblemen used to assemble in his khanqah, and as was usual in Jalaluddin’s regime, their discussions often veered around ways to depose the sultan. One such discussion dwelt on the possibility of making Sidi Maula the next emperor. This information reached the sultan, and all the plotters as well the saint were brought before him. While the noblemen were sent off to faraway provinces after he had confiscated their property, the saint’s fate was deliberated. Despite the vehement denials of the darwesh, and in spite of the sultan’s past record of lenient justice in similar cases, the poor man was trampled to death by an elephant. Barni says he remembers that day clearly when suddenly the sky became downcast with dark clouds. Famine hit the country that same year, and the price of grain shot up to one jittal per ser.

In 1292, there was a huge Mongol invasion by fifteen tumhans (or 1,50,000) Mongols but the sultan’s army was victorious. Here again, the sultan displayed exceptional clemency to the invaders, and they were allowed to go back home after exchanging gifts and rounds of buying and selling. However, thousands of the invading army sought the sultan’s permission to settle down in Delhi. New settlements at Kilughari, Ghiyaspur, Indarpat and Taluka were set up. The Mongols were rechristened as New Muslims, royal subsidies were extended to them, and even one of their areas of settlement was designated as Mughalpur (present day Mongolpuri).

Alauddin meanwhile proceeded to Deogir on a military expedition, without informing the sultan, and returned with a huge booty of gold, silver, jewels, elephants and horses. The news reached the sultan, and he became even more anxious to meet and congratulate his nephew. Alauddin seized the opportunity for finally eliminating his master. He invited him to Karra, giving the impression that he was afraid of being punished in Delhi for his supposedly defiant act of attacking Deogir. He asked the sultan to come down personally to bless him and accept all the war booty. The sultan thus induced, crossed the flood-ravaged plains with his army, and camped en route to Karra.

One of Alauddin’s accomplices met him there and asked him to leave his armed escorts behind and board a boat to cross the river. The gullible and kind sultan agreed to his son-in-law’s request, and as he alighted on the other side of the river, he embraced Alauddin, saying, “I have brought you up from infancy, why are you afraid of me?” Suddenly, on Alauddin’s signal, a few waiting men overpowered the old king and cut off his head. It is said that Ikhtiyaruddin, who cut off the head, very soon went mad, and often hallucinated that he was seeing Jalaluddin standing over him with a naked sword.

On hearing of her husband’s murder, Malika-I Jahan, the sultan’s wife, proceeded to the Green Palace in Old Delhi, and declared her youngest son, Ruknuddin, as the heir to the kingdom. However, his rule was very short, and they had to flee to Multan when Alauddin reached Delhi to ascend as the next Khilji sultan of Delhi.

Alauddin Khilji: The ‘First Real Emperor’ of India

Alauddin proceeded to Delhi with a great army, amassed through liberally scattering gold after covering every short distance, to attract people to join his march. On reaching Delhi, he again distributed purses full of jittals and tankas among the citizens, and soon he was accepted wholeheartedly by the noblemen and the population. Though he was an illiterate, soon he established himself as an able military leader, and victories over the Mongols and neighbouring provinces came in quick succession. By nature, he was a violent and cruel man, but certainly, success was inseparable from him. Caskets and boxes of gifts and jewels overflowed in the city. There were as many as 70,000 horses in the royal stable.

As success touched his feet, he thought of two grand schemes to make his name immortal: first, he wanted to promulgate a new religion and second, he wanted to go on a world-conquering expedition like a second Alexander. However, he shelved both these plans, and instead set out to subjugate Ranthambor, Chittor, Chanderi, Malwa, Dhar, Ujjain, Lahore, Dipalpur, and other provinces.

The ruthless trampling of thousands of captured Mongols by elephants, the decorating of fort walls and specially erected towers such as the Chor Minar with the severed heads of Mongol attackers, and the building of pyramids of heads, allowed him to reign for twenty long years, even under such a chaotic and unpredictable atmosphere.

Amir Khusrau’s poetic descriptions on such military expeditions against invading Mongols in his “Tarikh-I ‘Alai” using fanciful analogies of a chess board and the battle field, deserve to be quoted in full:

“He dispatched the late Ulugh Khan, the arm of the empire, with the whole of the right wing ( hand) of the army…The Khan sped swift as an arrow from its bowstring, and made two marches in one until he reached the borders of Jaran Manjur, the field of action, so that not more than a bow-shot remained between the two armies. That was a date on which it became dark when the day declined, because it was towards the close of the month, and the moon of Rabi’u-l akhir waned till it looked like a sickle above the heavens to reap the Gabrs. Arrows and spears commingled together. Some Mughals were captured on Thursday, the 22nd of Rabi’u-l akhir, in the year 695 H. ( Feb. 1296 A.D. ). On this day the javelin-head of the Khan of Islam fell on the heads of the infidels, and the standard-bearers of the holy war received orders to bind their victorious colours firmly on their backs; and for honour’s sake, they turned their faces towards the waters of the Sutlej, and without the aid of boats they swam over the river, striking out their hands, like as oars impelling a boat.”…

…“The field of battle became like a chess-board, with the pieces manufactured from the bones of the elephant-bodied Mughals, and their faces ( rukh ) were divided in two by the sword. The slaughtered hoggish Mughals were lying right and left, like so many captured pieces, and when thrust into the bag which hold the chessmen. The horses which filled the squares were some of them wounded and some taken; those who, like the pawns, never retreated, dismounted, and, advancing on foot, made themselves generals (queens). ‘Ali Beg and Turtak, who were the two kings of the chessboard, were falling before the fierce opposition which was shown by the gaunt bones of Malik Akhir Beg, who checkmated them both, and determined to send them immediately to his majesty, that he might order either their lives to be spared, or that they should be pil-mated, or trodden to death by elephants.”

Mutinies and the Sultan’s Four Bold Regulations

In early years, he faced as many as four revolts from his own men. The first was started by the Mongols, or ‘new Muslims’, in his army while on a military campaign to Gujarat. The following three revolts were equally serious in nature, occurring when the sultan was away at Ranthambhor. One was launched by his own nephew with the intention of killing him. After these four insurrections and military coups, he discussed ways to prevent similar mutinies in the future with his wise men and laid down four new regulations:

- Property confiscation: The population was subjected to many types of taxation and money extraction. Villages were brought under the state exchequer. People were so busy earning their livelihoods that no one could afford to harbour any plans for a mutiny.

- Increased surveillance: Spies religiously conveyed information regarding happenings among the amirs, general gatherings and the marketplace to the sultan, and severe punishments were meted out to suspected plotters.

- Banned wine: He prohibited wine drinking, dicing and wine parties, and he abstained from wine. Jars and casks of wine from the royal cellar and all china and glass vessels from the fort were brought out and broken near the Badaun Gate of the city, where the wine formed a muddy river. If any wine-sellers were caught, they were lowered into and buried in pits dug in the ground outside the Badaun Gate. Most of those punished in this way died in the holes, creating a strong deterrent. A few people who could not abstain travelled past the city borders beyond Yamuna, where enforcement was less strict.

- Prohibited the assembly of amirs: The great men and the nobles were prohibited from visiting each other’s’ houses and gossiping in the serais and other general assemblies.

Establishment of the New City – Siri:

The Mongol invader Targhi, when learnt that Allauddin was away from Delhi for a military campaign to Chittor, marched towards Delhi with twelve thousand cavalry, and camped near Jumna. The invading army seized all ingress and egress of Delhi and prevented any ration or reinforcement to reach the city. The sultan had just returned from Chittor, while his other generals were still away in another military campaign to Arangal.

Ziaud din Barni describes in his “Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi”: “The Sultan, with his small army of horse, left the capital and encamped at Siri, where the superior numbers and strength of the enemy compelled him to entrench his camp…The Mughals came up on every side, seeking opportunity to make a sudden onslaught and overpower the army. Such fear of the Mughals and anxiety as now prevailed in Delhi had never been known before. If Targhi had remained another month upon the Jumna, the panic would have reached to such a height that a general flight would have taken place, and Delhi would have been lost.”

However, the invaders withdrew after two months of siege. Legend has it that, when the Mongols were looting the granaries and the suburbs, the sultan had no option but to entrench himself. One day he visited Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya, and in the same night, commander of the invading army Targhi Beg panicked and withdrew from Delhi.

Here the ‘capital’ refers to the old city of Kila Rai Pithora, and suggests that the sultan encamped at a plain land called Siri which was outside the city, but a proper fort or city was nonexistent.

Barni says, “After this very danger, ‘Alau-d din awoke from his sleep of neglect. He gave up his ideas of campaigning and fort-taking, and built a palace at Siri. He took up his residence there, and made it his capital, so that it became a flourishing place. He ordered the fort of Delhi to be repaired, …”

The city was built at a distance from the older settlement of Kila Rai Pithora, and the space between the two was a suburb called Jahan-panah. Jahan-panah was originally unprotected, and a strong stone wall was built later on only by Muhammad-bin-Tughluq in 1326-27. Siri had seven gates, Old Delhi had ten, and Jahan-Panah had thirteen gates.

Timur describes the three localities of Delhi as on 1398 in his autobiography ‘Tuzak-I Timuri’ : “By the will of God, and by no wish or direction of mine, all the three cities of Delhi, by name Siri, Jahan-panah, and Old Delhi, had been plundered…Siri is a round city. Its buildings are lofty. They are surrounded by fortifications, built of stone and brick, and they are very strong. Old Delhi also has a similar fort, but it is larger than that of Siri.“

Finally, to quote Ibn Batuta, who was one of the Delhi’s magistrates thirty years after Alauddin’s death : “Dar-ul Khilafat Siri was a totally separate and detached town, situated at such a distance from old Delhi as to necessitate the construction of the walls of Jahan-panah, to bring them within a defensive circle; and that the Hauz-i-khas intervened, in an indirect line, between the two localities.”

As per Ain Akbari, when Sher Shah Suri constructed his new city of Dinapanah, he ransacked Siri and used the building materials to raise his new city. Araish-i-Mahfil records that Sher Shah also pulled down the famed “Green Palace”, or Kushak Sabz inside the ‘Old City’ of Kila Rai Pithora, in order to build Dinapanah.

It is said that the pride of the new city was the celebrated palace of Qasr-i-Hazar Sutun, or “Palace of One Thousand Pillars”, built outside the fort premises. But, it has not yet been possible to pinpoint a location where this exquisite palace once stood, leave aside finding any of its remaining. It is also not clear if the same building is being referred while recalling the similarly-named building by Muhammad-bin Tughluq, and described by Ibn Batuta.

After the decision to erect the Siri Fort was made, Alauddin also planned to raise a large, well-horsed, mounted permanent army to guard against the Mongols, at a fixed salary of 234 tankas, which was a meager amount in those times. The wise-men of his court were then consulted, and it was decided that in order to maintain a large army at a low cost, the market prices must be strictly regulated, so that even this low salary would be sufficient for a citizen.

It is said that Alauddin’s successor Qutbuddin later erected a new mosque inside Siri, and as per prevalent customs, he required all the saints and learned men of Delhi to come and offer prayers at the new mosque on its opening day. However, Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya turned down the invite saying that he has his own mosque to offer prayers. He also refused to go to the sultan’s court to greet him on the first day of the lunar month, as per the customs, and in stead sent his assistant to the court. The sultan was infuriated, and declared that the saint would be punished if he fails to turn up on the next lunar month. It so happened that on the very morning of the first day of next lunar month, the sultan was killed by his favourite slave, Khizr Khan. Presently, only ruined stretches of the rubble wall that once surrounded Siri, along with collapsed bastions, are all that exist. Out of its original seven gates, only one on the south-eastern side has come down to us.

Banking and Coinage System

The sultan then promulgated a number of regulations to control prices in the markets, so that he could maintain a permanent mounted army at an affordable cost. He fixed the prices in market as

wheat at 7.5 jittals per maan,

barley at 4 jittals per maan,

rice at 5 jittals per maan, etc.

The prices for slaves were fixed as:

serving girls at 5–12 tankas each,

concubines at 20–40 tankas,

domestic slaves at 17–18 tankas,

male slaves at 100–200 tankas, etc.

During Alauddin’s rule, Jains played a major role in minting, banking, exchanging money and assaying. Assaying is used when exchanging money. There were many types of coins issued by various sultans and kingdoms, but there were no official exchange rates for the different currencies. The assayers or money changers used to facilitate the exchange by determining the amount of gold or silver in a coin. This was done using a touchstone (kasauti in Hindi) or by melting. When a gold or silver object is rubbed against a touchstone, it leaves behind a streak of fine powder whose colour varies depending on the purity. The colour of the streak is compared to a set of gold or silver reference bars with varying purity, and the worth of the coin is then determined.

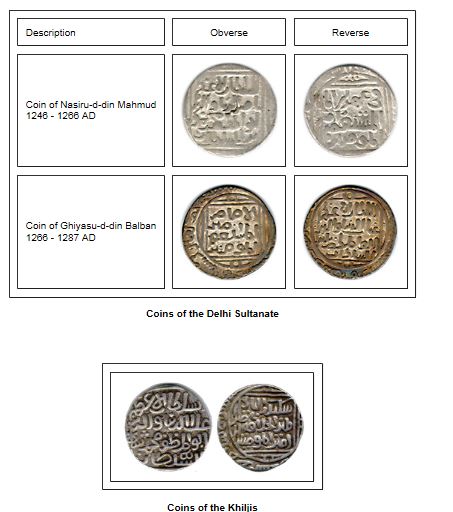

( Coin samples from Slave and Khilji Era, Courtesy – RBI Monetary Museum, Mumbai, Reproduced with kind permission)

( Coin samples from Slave and Khilji Era, Courtesy – RBI Monetary Museum, Mumbai, Reproduced with kind permission)

Thakkura Pheru, belonging to a Jain family from Haryana, was the assay master at the Delhi Mint. He wrote that he had direct experience of examining gems “during the victorious reign of Alauddin,” and had “seen with his own eyes the vast ocean-like collection of gems in Alauddin’s treasury.” He authored a number of books, of which Dravya-pariksha written in 1318 in verse form in the Apabrahmsa language is quite unique. In this book, Pheru describes about 260 types of coins issued by the various kingdoms of north India in the twelfth, thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. He gave their name, weight, metal content and exchange value in terms of the Khilji currency.

Pheru calls this type of money exchange nanavatta, and people who practise nanavatta are called nanavati. This survives as a surname today in western India. Apart from Nanavati, a few other surnames of today can also be traced back to the profession of assaying, such as Parikh and Parekh (from the Sanskrit word parikshaka), and Poddar and Potdar (from the Persian word fotah-dar).

(*please see Side Note 2 for a further short summary on coinage and banking)

Keeping an Hawk’s Eye on Market Matters

To keep a tab on market malpractice so that market prices remained under control, the sultan used to send poor ignorant children to buy various things from the market, such as grains. The items were weighed in the presence of the superintendent, and if the weight was short, the seller was tracked down, and an equal weight of flesh was cut from his body, and thrown down in front of everyone. Even for trivial items sold in the market, he wanted three reports: one by the market superintendent, the second by official reporters, and the third by spies. If there was any discrepancy among the three, the superintendent was taken to task.

Spies were employed to check if any marketer was selling their goods – grains, or anything from caps to shoes, and from needles to combs – at prices that were too high. All villages were ordered to send by caravan half of their produce to the royal granaries in Delhi. As a result, there was never any shortage of grain in the city, even if there was a drought, or if some of the caravans were delayed in reaching the city. The caravans and the transporters were kept under strict supervision by the controller of the markets. Black marketing and diverting grains and corns were also minutely scrutinised.

Military Triumphs of the Khilji Sultanate

With the tariffs thus controlled, a large army could effectively be maintained at an affordable cost, and the sultan successfully thwarted numerous Mongol invasions. The defeated Mongols were beheaded and towers were erected outside the Badaun Gate from their heads. Many were trampled by elephants, and many were brought to Delhi with ropes tied around their necks.

Ghazi Malik, who later established the Tughluq Dynasty in Delhi, was appointed as the general of Lahore and Dipalpur. He was hugely successful in driving out the invading hordes of Mongols on the western front. As a result, the Mongols entirely gave up any ambition to raid Delhi further while Alauddin was alive.

During military expeditions, the sultan arranged a network for gathering information in near real time: relay horses were stationed at every post, runners were positioned at a distance of every half or quarter kos, and every town had official report writers.

Closer to home, he subdued provinces and spread the Delhi Sultanate for the first time into the deep south, including Deogir, Arangal and Ma’bar. The army returned from Ma’bar in 1311 with 612 captured elephants, 96,000 maans of plundered gold, 20,000 horses and innumerable boxes of jewels. He is credited with the acquisition of the famed Kohinoor diamond from the Kakatiya rulers of Warangal.

The war spoils were presented to the sultan at the newly built red fort of Siri, and he distributed money and gold to his amirs and maliks. The citizens of Old Delhi remarked that never before had they seen such a large number of elephants and such a huge amount of gold in Delhi.

Barni summarised the major successes of Alauddin’s reign as:

- Low prices in the markets and a low cost of living

- Constant succession of victories

- Destruction of Mongol invasions, resulting in peace and tranquillity

- Maintenance of a large army at a very low cost

- Successful suppression of rebellions and revolts

- Honesty in markets

- Repair and commissioning of forts and mosques, and excavation of tanks, etc.

The sultan breathed his last in 1316 in his new capital city of Siri. The Khilji Empire was tottering and serious revolts were being reported from various provinces.

Barni writes, “On the sixth Shawwal, towards morning, the corpse of Alau-d din was brought out of the Red Palace of Siri, and was buried in a tomb in front of the Jami Masjid.”

Khilji Architecture and Monuments

Alauddin Khilji is the only Khilji sultan to have left an impressive architectural heritage in Delhi. As the Mongols devastated cities throughout Central Asia, artists, poets, architecture planners and Sufi saints fled the Mongol onslaught and migrated to other places, including to Delhi, where they helped shape Delhi’s culture and raised its architecture to a new zenith.

Alauddin set up the new city of Siri, extended the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, commissioned the exquisitely beautiful Alai Darwaza, started erection of the massive Alai Minar and excavated Hauz-i-Alai lake at Hauz Khas as a water source for Siri. Also, during his reign, his son built the Jama’at Khana Masjid near the tomb of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, in a similar architectural style to that of Alai Darwaza.

Feristha recorded the proliferation of buildings during Alauddin’s reign, writing, “Palaces, Mosques, Universities, Baths, Mansolea, Forts, and all kinds of public and private buildings seemed to rise as if by magic.”

Architecture under the Khiljis acquired a certain grace, maturity and proportion in its buildings. The innovative use of red-coloured sandstone was introduced for the first time to break the deathly monotony of grey buildings. The early days of Islamic architectural experimentation were now over and new mature innovations, including broad domes, large horseshoe-shaped true-arches, recessed arches under squinches, lotus-bud fringes on the underside of arches, decorative mouldings and perforated windows, etc. were confidently incorporated in the designs of the Khilji architects.

Presently, the original location of the Siri Fort still retains some of the Khilji-era monuments, as well as a few latter-day constructions from the Tughluq and Lodi dynasties, including:

- City Walls of Siri ( Rubble Built / Khilji) – Shahpur Jat, Asiad Village

- Stone Bridge ( Khilji ) – Shahpur Jat

- Chor Minar ( Rubble Masonry / Khilji) – Hauz Khas

- Iqbal Khan’s Idgah ( Rubble Masonry / Late Tughluq ) – Hauz Khas

- Makhdum Shah Mosque ( Plastered Rubble Masonry & Local Grey Stone / Lodi) _ Mayfair Gardens

- Tohfe Wala Gumbad ( Rubble Built / Khilji) – Shahpur Jat

- Muhammadi Wali Mosque ( Dressed Hard Stone & Red Sandstone / Lodi) – Siri Fort Sports Complex

8. Mosque of Darwesh Shah ( Rubble Masonry / Lodi ) – across Gulmohar Park

Fort Walls and Stone Bridge:

Very little remains of the magnificent city that Alauddin built save for a few stretches of its rubble-built wall. A few stretches still have the original bastions and loopholes can still be seen in the walls, although they are mostly in a dilapidated state. Siri Fort’s old walls can still be seen in Shahpur Jat, Siri Fort residential area, Panchsheel Park and Asiad village. The city was said to draw water from the nearby lake excavated by Khilji, which was known as Hauz Alai, and that has been re-watered in recent times and is now known as Hauz Khas lake. The city was probably surrounded by a moat, and evidence of this can be seen from the remains of a small stone bridge with three vaulted chambers, which can be found near the remaining part of the wall.

Chor Minar

Located in the Hauz Khas area; this is a tapering tower with a base diameter of 21’ and a top diameter of 18’, sitting on a 7’ high platform. It has a set of three arches punctured on each side of the raised platform, with a single entrance situated on its east facade. A spiral staircase is provided within the Minar, but the access to it is now locked. It was built by Alauddin Khilji. It is said that the heads of slain prominent Mongol invaders or local chieftains were regularly hung from the 225 holes on its outer side. This is a macabre privilege of sorts as only the heads of the generals of the invading army or of the chiefs of local tribes could make it to the tower, while the heads of ordinary soldiers and thieves were arranged in a more common ‘pyramids of heads’.

Its original use, however, is still shrouded in mystery, although some accounts claim that the structure could have been built as a hunting lodge, or as an observatory. But no historical literature contains any reference to the structure so we cannot confirm its real purpose.

Its original use, however, is still shrouded in mystery, although some accounts claim that the structure could have been built as a hunting lodge, or as an observatory. But no historical literature contains any reference to the structure so we cannot confirm its real purpose.

Iqbal Khan’s Idgah

The interesting story of the Idgah, situated in the upmarket Hauz Khas locality in South Delhi, is easier to ascertain as it is written in an inscription fixed on its south bastion on a red sandstone slab. The inscriptions states:

“In the name of God who is merciful and clement. When the pious city of Delhi, the metropolis of the country, was desolated by the evil of the accursed Mughals and the mischief of infidels and satans, and had become an abode of wild beasts and birds, and the mosques, schools, convents, places of worship and all the charitable foundations were deserted; by the Divine favour and the grace of the Lord, the slave of God named Iqbal Khan, alias Mallu Sultani, had the divine guidance and good fortune, in that he was able by great efforts and endeavours to restore all the charitable foundations, and repopulate the capital of Delhi, and other parts of the country. He also built this place of worship, which is one of the things necessary for the Muhammadan religion, and is enjoined to be built by the Divine law, with his own money, so that the Muhammadan public should be benefited by it, and bless the founder, on the 16th of the month of Shaban – may its blessings be universal, the year 807. The erection of this religious building has been under the direction of the slave Dilpasand Khani.”

This is a fascinating monument of the late Tughluq era, from when Timur had just devastated Delhi, and the city ‘had become an abode of beasts and birds’.

It is a Idgah, or Eid-gah of rubble masonry wall-mosque facing the customary westerly direction, containing eleven recessed mihrabs , with a large courtyard in front for people to assemble and offer their prayers on Eid, and circular bastions at either end. Only the bastion on the left stands today facing south, while its opposite bastion has collapsed. A thirteen-step staircase adorns its centre.

It was built by Iqbal Khan, who calls himself ‘Sultani’, i.e. Slave of the last Tughluq Sultan Mahmud Tughluq, in the year 1404-05 A.D. Timur had just ransacked Delhi in 1398, and both Iqbal Khan and Mahmud Tughluq had fled from Delhi: Iqbal Khan to Baran or Buland Shahar, and Mahmud Tughluq to Kanauj. Iqbal Khan retuned to Delhi a year later in 1399-1400 A.D. and built this Idgah, and tried to repopulate Delhi. Mahmud Tughluq returned a year after him, in 1401-02 A.D., but the power still remained with Iqbal Khan.

Dipasand Khani was the eunuch slave of Iqbal Khan who supervised the building of the Idgah.

Makhdum Shah Masjid

This is located inside a picturesque setting, nestled between the very posh Mayfair Gardens bungalows of South Delhi. It is as if the neat new bungalows have respectfully been nurturing the aged monument.

Named after the saint Makhdum Sahib, the Masjid stands amidst a number of unknown graves within a walled enclosure.

Its central prayer hall has seven bays, with domes sitting on the central part, as well as on the corner bays. Projecting mihrabs mark its western side.

There are two side-compartments on both the left-hand and right-hand side facing north and south of the prayer chamber, and both these compartments extend towards the front, i.e. towards the east, forming an inverted U-shaped structure. The end of both the eastern extensions are domed tombs, which, , with sunlight filtering through their intricate sandstone screens, might have been built for solitary meditation.

The grave of the saint Makhdum Shah lies under a balcony with arched cells. Patches of beautiful blue inlay work can be seen on the inside, and it must have truly looked beautiful in earlier days. Small mini-minarets adorn the four corners of the chattri. Surrounding the saint’s grave under the canopy, there are numerous big and small graves, just like at Nizamuddin Dargah, and they are decorated profusely with flowers by Hindus and Muslims alike. These are likely the graves of the saint’s followers.

The entrance gateway is built in a Hindu architectural style of corbelled arches, with a dome surmounting the square gateway. There are no minarets for the muezzin to call and address the gathering for prayer.

Tohfewala Gumbad

This is located in the Shahpur Jat area. With residential blocks surrounding the stout dome from all sides, it stands on overgrown grassland within a walled enclosure. Local children can be found cycling inside the tomb and in front of its mihrab wall.

Originally it formed the central prayer chamber of a mosque, which is now non-existent. Three recessed mihrabs adorn the western walls of this square structure, surmounted with a dome. The arched entrance gateway is on the opposite eastern side, with similar arched openings piercing its north and south sides, on the left and right of the mihrab wall.

Although the name of this Khilji-era monument suggests ‘a gifted tomb’, it is not known who actually built this, and as a gift for whom.

Muhammadi Wali Masjid

This masjid is located near the entrance of the Siri Fort Sports Complex. It is accessible through a long patch of rolling grassland, with the remnants of the Siri Fort walls on one side, and the collapsed bastions neatly restrained by modern conservation. Scores of peacocks can be found ambling around the grassland, and playing hide and seek behind the walls.

Designed like the Isa Khan Tomb, it stands amidst a number of unknown graves within a walled enclosure.

Its main entrance on the south wall consists of a dressed hard stone gateway, enclosed by an arch of red sandstone. The tomb has three bays, with the central bay adorned with a dome surmounted on an octagonal drum. Three recessed mihrabs mark its western side, with the central one in red sandstone. Traces of blue tile decorations can be seen on its eastern façade, which is punctured by three archways. On the top of the archways, heavy stone brackets project outwards, supporting a chajja. Its interiors are pleasingly decorated with an abundance of intricate incised plaster (stucco) medallions.

A stairway to the roof is situated on its south side.

Mosque of Darwesh Shah

This mosque is located in a park opposite Gulmohar Park on the road from the Siri Fort Auditorium, with jogging tracks and walkways criss-crossing the green patch. Designed in a rectangular plan with an enclosed courtyard, its west and east side have seven arches each. Its western wall represents a wall-type mosque, with seven recessed mihrabs, with the central one being a projected type with flanking minarets. Both the left and right sides of the wall mosque, i.e. its north and south sides, have five arches each. The whole structure sits on a raised platform.

Nothing is known of the ‘Darwesh’, which means a Saint, by whose name the mosque was built.

Nothing is known of the ‘Darwesh’, which means a Saint, by whose name the mosque was built.

—————————————————————————————–

Side Note 1: Kilokhri – Another Delhi Erased by Time

Siri is said to be the first capital city of Delhi to have been built by Muslim rulers, and was called at that time Darul Khilafat, or the Seat of the Caliphate. It was a major capital city of Delhi, that is true, but we must also give some credit to a lesser known city, Kilu-ghari or Kilokhri. This was a small town, and preceded Siri by a few years. It was raised in 1286-87 A.D. by Moizzu-d-din Kaikubad, the successor to Balban, and the last of the Slave sultans.

Kilokhri was one of Delhi’s many older cities. Barni narrates, “ Sultan Muizzudin gave up residing in the city, and quitting the Red Palace, he built a splendid palace, and laid out a beautiful garden at Kilokhri, on the banks of the river Jun (Jumna). Thither he retired, with the nobles and attendants of his court, and when it was seen that he had resolved upon residing there, the nobles and officers also built palaces and dwellings, and, taking up their abode there, Kilokhri became a populous place.”

Sultan Kaikubad breathed his last in his new city Kilu-ghari, where he was lying sick in his last days in the Room of Mirrors. Meanwhile the Khilji supporters were growing in numbers in the city. A malik whose father had been sentenced to death by the sultan was sent into Kilu-ghari to finish him off. The malik entered the Room of Mirrors, and seeing the dying sultan, delivered him two or three kicks, and threw his body into the Yamuna.

Immediately, Jalaluddin was escorted from Baharpur and was seated on the throne in Kilu-ghari. The first Khilji sultan, Jalaluddin, also made it his capital city, as he was averse to going to Old Delhi, fearing the resistance of its people, whom he considered loyal to the Turkish Slave Dynasty.

Barni writes, “ In the course of the first year of the reign, the citizens and soldiers and traders, of all degrees and classes, went to Kilu-ghari, where the Sultan held a a public darbar. He ordered the palace, which Kai-kubad had begun, to be completed and embellished with paintings; and he directed the formation of a splendid garden in front of it on the banks of the Jumna. The princess and nobles and officers, and the principal men of the city, were commanded to build houses at Kilu-ghari. Several of the traders were also brought from Delhi, and bazaars were established . Kilu-ghari then obtained the name of ‘New Town’. A lofty stone fort was commenced, and the erection of its defences was allocated to the nobles, who divided the work of building among them. The great men and citizens were averse to building houses there, but as the Sultan made it his residence, in three or four years, houses sprung up on every side, and the markets became well supplied.”

Today, only a similarly named village called Kilokari exists around Sunlight Colony in Delhi, with no trace of any palace or monuments of erstwhile Kilu-ghari or Kaiqubad, except the grave and mosque of the great Sufi saint Khwaja Sayad Mahmud ‘Bahaar’, one of the twenty-two Khwajas of Delhi. The mosque is hidden behind apartment blocks and shopfronts, almost squeezing the already narrow lanes leading to it.

Sayad Mahmud ‘Bahaar’ was the contemporary of Khwaja Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya. He is credited with many miracles, and he died in 778 A.H. (1376–77 A.D.). The grave lies under a canopy, with an enclosing wall, which are believed to be of modern construction. An old man whom I met at the mosque informed me that his family is the seventieth generation of the revered saint. A domed building of rubble masonry, most probably an ancient gateway to the grave enclosure, is situated nearby.

———————————————————————————————–

Side note 2: Numismatic history of the Khilji Sultanate

These early Muslim rulers believed the following two supreme things gave them the right to rule and used them to impose their authority:

- Reading their name in Khutba or public prayers

- Inscribing the ruler’s name on coins

Rulers issued coins from places and territories after they annexed or occupied them for commemorative purposes. For example, Iltutmish issued coins from Delhi and Razia issued them from Lakhnauti (Bengal). Alauddin Khilji issued coins from Deogir and Ranthambhor after capturing them. However, he changed the name of Ranthambhor to Darul-Islam, and the coins were issued in that name. Alauddin Khilji made some important changes in his coinage system.

- Dropping the names of Khalifas from coins :

Earlier Muslim rulers followed the practice of imprinting the names of the Khalifas of Syria on their coins, but Alauddin discontinued this trend. Instead, coins issued under Alauddin were marked with grandiose titles, such as sikandar al-thani (“the second Alexander”), yamin al-khilafa (“the right hand of the Caliphate”) and nasir amir al-mu’minin (“helper of the Commander of the Faithful”). It is likely that while Muslim mint-masters were responsible for ensuring that such religious titles were correctly used on the coins, the Jains handled the technical matters of the coinage system.

- Issuing gigantic coins:

He issued gold tankas weighing 5, 10, 50 and 100 tolas. His successor, Qutbuddin Mubarak Shah, issued gold and silver tankas weighing 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 150 and 200 tolas. One tola equalled 11.003 grams, so a 100-tola tanka would have weighed over one kilogram. Experts believe these gigantic tankas were huge ingots with artistic impressions used for imperial gifting purposes and as souvenirs.

- Equal Weight Coins:

The unit coins were known alternatively as kani, gani, jittal, jaithal, dramma or dam. They were referred to as jittals/jaithals in pre-Khilji times; they became known as dam or dramma during the Khilji reign.

Various jittal/damma/gani coins were :

1 (eggani),

2 (du-gani),

4 ( chau-gani),

6 ( cha-gani),

8 (atha-gani),

12 ( barah-gani),

24 (chaubis-gani), and,

48 (adtalisa-gani)

As per Thakkura Pheru, these coins were differentiated as per the composition of copper and silver in the coins.

For example, Eggani = 95% copper + 5% silver

Du-gani = 90.25% copper + 9.75% silver

Chau-gani = 83.6% copper + 16.4% silver, and so on.

Interestingly, the coins upto the ath-gani were of same uniform weight of 56.7 grains. Also, they did not have their value inscribed on their surface, so it is still a mystery as how the common people could differentiate them in daily use, or if these coins of different metal composition represented different denominations at all.

Above the unit coin of ganis, the tanka was defined.

Incidentally, the name Tanka survives even today as Taaka which is the name of currency of Bangladesh.

One Tanka = 60 gani

Weight of 1 silver Tanka = 1 tola = 11.003 grams

Weight of 1 jittal/gani = 1/12 tola = 0.917 grams

Below the gani, the copper coins of lesser denominations were defined as

Visua / visuva = One-twentieth of a gani

Sava-visua = One-sixteenth of a gani

Adhava = one-eighth of a gani

Paika = one-fourth of a gani

———————————————————————————————

My deepest gratitude to Prof S R Sarma, Dusseldorf, Germany for his guidance on Khilji-era coinage and banking system.

Thanks to Aradhana Sinha, of INTACH Delhi Chapter for leading the exploration of ‘Siri – the Second City of Delhi’ and nearby monuments.

References:

- The History of India, as told by its own historians (Vol III) by Sir H.M. Elliot & John Dowson, 1871, London.

- Alexander Cunningham: Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64 ( Volume I); Archaeological Survey of India, 1871, New Delhi, reprinted 2000.

- Delhi and its Neighborhood, by Y.D. Sharma, Archaeological Survey of India, 1964, New Delhi, reprinted 2001.

- A Jain Assayer at the Sultan’s Court, by Prof. S.R. Sarma, 2001 (http://s523025865.online.de/Nandu/SRS/pdf/articles/2012_Jain_Assayer.pdf)

- List of Muhammadan and Hindu Monuments, Volume III & IV, Maulvi Zafar Hasan, J.A. Page & J.F. Blakiston, 1922, A.S.I., Calcutta

- Coins of Khilji Era, from Reserve Bank of India Museum: https://www.rbi.org.in/currency/museum/c-medi.html

- A Guide to Nizamu-d Din, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India ; by Maulvi Zafar Hasan, 1922 (Reprinted 1998), ASI, New Delhi.

- Coins, by Parmeshwari Lal Gupta, 1969, ( 2013 reprint), New Delhi.

- Invisible City-The Hidden Monuments of Delhi, by Rakhshanda Jalil, 2008 ( Reprinted 2014), New Delhi.

- Cities of Delhi, by Vikramjit Singh Rooprai : http://www.monumentsofdelhi.com/Cities

- Monuments of Delhi, by Archaeological Survey of India http://www.asi.nic.in/asi_monu_alphalist_delhi.asp

- Map of South Asia in the time of Khiljis and Tughluqs : http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/schwartzberg/fullscreen.html?object=075

- Twenty Two Khwajas of Delhi : http://www.thedelhiwalla.com/2013/10/04/city-list-22-sufis-around-town/

- Qasr-i-Hazar Suton, by Madhu Singh : http://www.madhukidiary.com/qasr-i-hazar-sutun/

My goodness. Never seen such detailed and accurate post on this city. Thanks for sharing Deb.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Vikramjit Sir

LikeLike

Excellent! Well written, giving a lot of details, a pleasure to read! Expect to see all these posts on Delhi collected up and issued in a book form?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sir,

God willing, I will definitely try to publish, maybe after more research to bridge my understanding gaps.

LikeLike

Very well written article

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot

LikeLike

Wow, you really do write well! Amazing! My only suggestion would be to make it a little shorter! But the detail and the history is great!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot Shireen! Will surely think of how to shorten posts as well to maintain continuity.

LikeLike

Very well written. I loved it. Alai would be proud!

LikeLike

Thanks. Hope you will share your feedback/improvement suggestions on other posts as well.

LikeLike

incredible monuments of Khilji era

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Awesome details!

Thanks!

Research is great!

LikeLike

Thank you a lot. Comments trigger me out of my laziness:) Sorry for late response

LikeLike

Very well articulated! Simply Brilliant!

LikeLike

thanks a lot Abhijit, really appreciate your reading and leaving a comment to motivate me

LikeLike