The City and the Citadel:

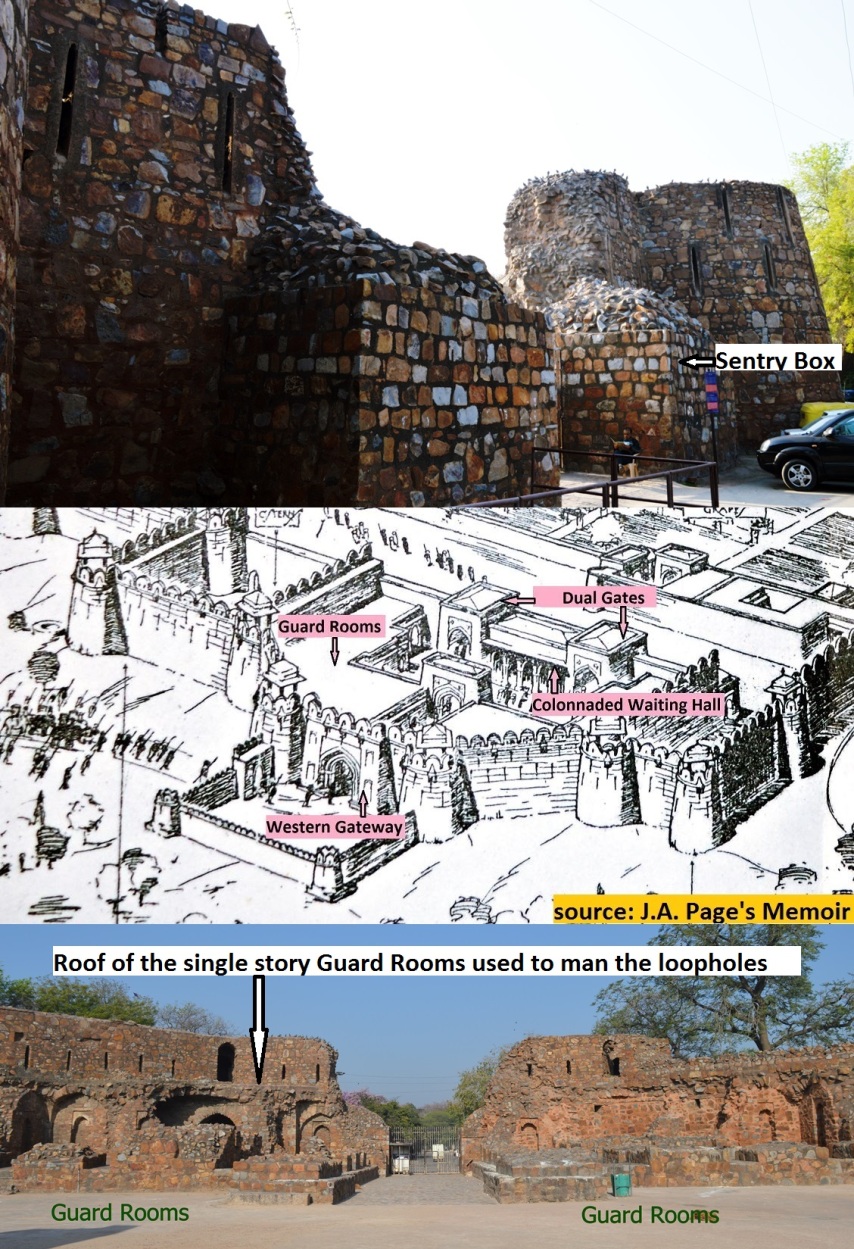

Imagine some 650 years back on a Friday, a stream of people arriving at the main western gateway – flanked by a bastion on either side – of the newly constructed city, by various means of transport : a mule, a carriage, or even by a palanquin; alighting under the careful gaze of the soldiers standing on the bastions and the parapet of the massive wall curtain, pierced by loopholes for use by the arrow-dischargers, being scrutinized and escorted by the guards into the colonnaded waiting hall, where they will have to wait their turn, listening to the distant gong of the exotic Tas-i-Ghariyal announcing the time of the day, and casting their appreciative glances on the ornamented and decorated slaves on palace duty. Shortly they would enter one of the two smaller gates into the palace interiors, meandering past the Garden of Grapes, to either the Ashoka Lat & the imposing Jami Masjid; or the Public Court of Audience – the Mahal-i bar-i ‘amm. Little imperial children clothed in white robes would be standing on the terrace of the Zenana Mahal with their mothers, screened by huge crimson shamianas to block the view from the public court below, watching flocks of chirping birds descending to the pigeon-nest on the eastern wall, while enjoying the cool of the river just a flight of stairs below. Since it is a Friday, parties of musicians, athletes and story-tellers from all the 4 suburbs of Delhi now must also be assembling at the main entrance.

( © A.S.I., New Delhi.

These images have been reproduced with the permission of ASI. It appears at Plate II & III in their publication: MASI No. 52, A Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi, published by Archaeological Survey of India, 1937, Reprint 1999. )

People from Delhi used to travel to the new city for pleasure trips and sight-seeing, and a variety of transport options were available for this purpose. Per person carriage fare was fixed at 4 silver jittals, a mule ride costed six jittals, twelve jittals for a horse-ride, and half-a-tanka for a palanquin.

The entrance to the citadel from the western side led to a waiting hall flanked by dual gates. Single-storied guard rooms lined the entrance interiors. The crowning merlons or kanguras on the wall are long gone, two rows of loopholes pierce the wall curtain: interestingly there is no evidence of any parapet for the arrow dischargers to stand on, and most probably some sort of timber staging was used.

The citadel of Firozabad was once surrounded by numerous new buildings in those times, including one private mosque and 8 public mosques large enough to accommodate 10,000 people each.

( © A.S.I., New Delhi.

This image has been reproduced with the permission of ASI. It appears at Plate II in their publication: MASI number 52, A Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi, published by Archaeological Survey of India, 1937, Reprint 1999. )

One of the great sights for the locals to gawk at was the Tas-i-ghariyal – a time measurement device, installed by Firuz Shah, using water clocks to notify correct time for prayers and breaking of Roza, etc, even in cloudy weather and after sunsets. Tas-i-gharial was basically a copper bowl ( ghati) with a small hole at the bottom. When this bowl is placed on the surface of the water in a larger vessel (kunda), water enters the bowl through the bottom. The weight of the bowl and size of the hole can be so adjusted that the bowl sinks after a specific period of time. When the bowl is full, it sinks with an audible thud, sixty times in 24 hours, and its each immersion denotes a lapse of one ghati, or 24 minutes; and a man on guard would strike a gong – called a gharial. Fraction of the ghati can be measured by dividing the bowl, for example, into 6 parts of 4 minutes each; and so on. The principle of Tas-i-gharial is mentioned and described in Abul Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari, but similar detailed information on Firoz Shah’s Tas-i-gharial from Tarikh-i-Firozshahi remains un-translated and unknown.

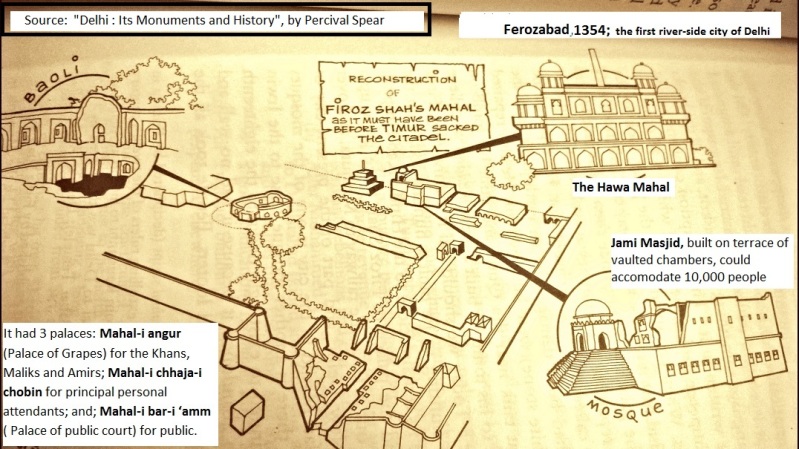

In this new city complex, there were three palaces exotically named as:

Mahal-i angur ( Palace of Grapes) for the Khans, Maliks and Amirs;

Mahal-i chhaja-i chobin for principal personal attendants; and;

Mahal-i bar-i ‘amm ( Palace of public court) for the public.

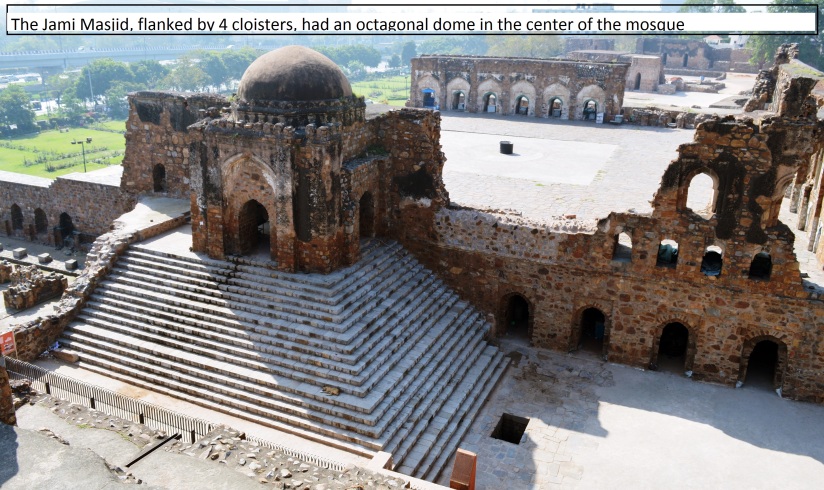

The Jami Masjid had four cloisters arranged in a rectangle, its small domed roofs supported on 260 stone columns of 16 feet high each; and having a 25 feet high central octagonal dome – that contained the Emperor’s ordinances – in the middle of the courtyard supported on a circular shaft. It must have been felt necessary to build a northern entrance gateway, rather than from the customary eastern side, because the river ran along its eastern edge. Narrow staircases for the zenana were present in the thickness of the western wall.

Timur was so impressed with the Masjid that he carried with him the sculptors, stone-masons and stucco-workers to build a similar mosque back home in Samarkand in December 1398. The layout of the Kotla Masjid was adapted to build his colossal Bibi Khanum Mosque at Samarkand – ‘whose dome would have been unique had it not been for the heavens, and unique would have been its portal had it not been for the Milky Way ’ – by the same Indian workmen from 1399-1404, using 95 elephant loads of exquisite precious gems and marbles and construction materials ferried from India, Samarkand Jami mosque’s vaulted roofs were supported on 480 marble pillars, with slender minarets at each corner, its walls and brass doors inscribed with Koranic verses.

Timur was so impressed with the Masjid that he carried with him the sculptors, stone-masons and stucco-workers to build a similar mosque back home in Samarkand in December 1398. The layout of the Kotla Masjid was adapted to build his colossal Bibi Khanum Mosque at Samarkand – ‘whose dome would have been unique had it not been for the heavens, and unique would have been its portal had it not been for the Milky Way ’ – by the same Indian workmen from 1399-1404, using 95 elephant loads of exquisite precious gems and marbles and construction materials ferried from India, Samarkand Jami mosque’s vaulted roofs were supported on 480 marble pillars, with slender minarets at each corner, its walls and brass doors inscribed with Koranic verses.

The circular Baoli – the King’s personal swimming pool which had considerable ornamental display of water conveyed from two overhead water tanks surmounted with chattris ; the ruined Jami Masjid; and the 42-feet and 7-inches high pale-pinkish tapering Ashokan pillar, whose golden ball and crescent at the top was still existing till 1611: are the only remnants of the Sultan’s most ambitious construction project, a cityscape which became the prototype for the later cities of Delhi: while the river fronted city, and the division of royal courts into three separate palace complexes as per the ranks of those attending it, was adapted by Shah Jahan for his city of Shahjahanabad; the rectangular lay-out of the innovative Jami Masjid became the pilot for not only the grandest mosque of Samarkand, but also to other contemporary Tughluq Mosques.

When Firoz Shah took over, Tughluqabad was suffering from acute water shortages, and Jahanpanah was a mere wall surrounding various settlements; so it was thought proper to raise a New Delhi. The fifth city of Delhi, Firozabad, was soon born in 1354 on the banks of the Yamuna, the first river-side city of Delhi. A fortified boundary wall protected its inner citadel while the city proper extended from Hauz Khas to Pir Ghaib. Important monuments like the Kalan Masjid, Khirki and Begumpur Masjids must have been within its city premises. Building material from Siri, Jahanpanah, and Qila Rai Pithora were used in the construction of Firozabad.

The city limits are extremely difficult to trace now, as Shahjahanabad was built later at a very short distance, allowing residents to re-use the building material. Roughly the city was built in a semi-circle of 1.5 miles radius around the Kotla center-point. Houses spanned across later-day Daryaganj, and along Chandni Chowk upto where the Lahore Gate was built later. While in later days, Ali Mardan Khan extended Firoz Shah Tughluq’s Hisar canal to Shahjahanabad, there existed another canal from Firoz’s times – heading from Yamuna through the Kotla citadel into the Firozabad city through the area of Faiz Bazar in Daryaganj. Firozabad was a basically a collection of suburbs like Siri, Jahanpanah, Delhi but without a boundary wall along its outer contour and thus open to potential attacks, which might have prompted Sher Shah Suri in later years to build a defensive wall, but could not be completed due to his very short stint.

After Feroz Shah died in 1388, subsequent kings re-used the building materials from the Kushk-i-Feroz, the ‘Citadel of Firoz’ – built from rough masonry of local quartzite stone blocks, to raise Newer Delhis – projects like Sher Shah Suri’s ‘Shergarh’ and Shahjahan’s ‘Shahjahanabad’ completely cannibalized the older city of Firozabad.

It is the Firoz Shah Kotla ruins where the Mughal Emperor Alamgir II (1754-59) was lured to death by his commander-in-chief by telling him that a noted Fakir has come there, and as the pious Emperor entered the place, hired assassins attacked and cut off his head, and threw the headless body from the mosque onto the river banks where it rotted for days.

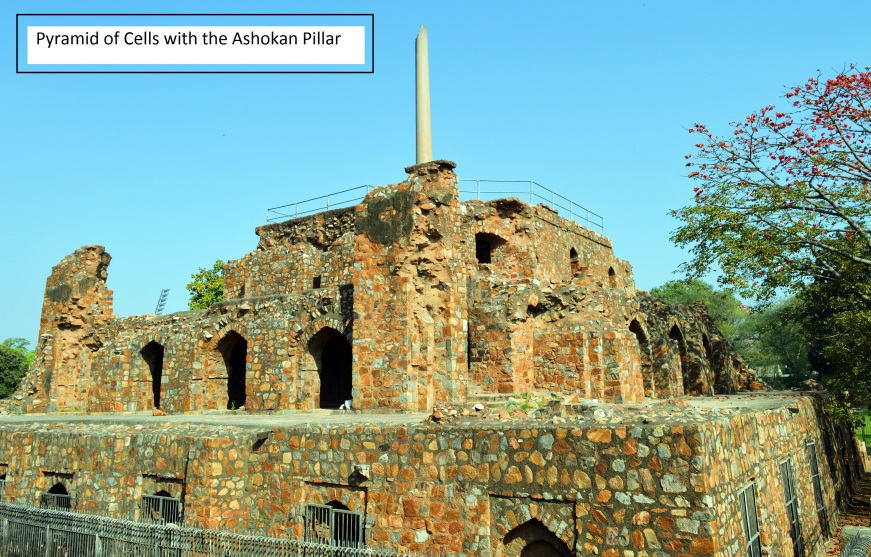

The Ashokan Pillar:

Impressed with discovering two Ashokan pillars during his hunting expeditions at Tobra and Merut near Delhi, Firoz Shah arranged to transport them to his new capital and installed them at Firozabad and at Kushk-I Shikar. These pillars were described by chronicler Afif as walking sticks of Bhim.

The Ashokan pillar is installed on top of a three-storied lofty rubble-built pyramidal structure with progressively diminishing size in each successive terrace, having cells with arched entrances, and referred to as the Hawa Mahal. The pillar is a 27-tonne sandstone monolith 42’ 7” in height – pale orange with flecks of black – out of which 35’ is polished. The unpolished portion is believed to be the buried part at its original place of installation at Tobra.

The great Mauryan King Ashoka reigned from 272-232 BC, therefore the pillar is roughly 2200 years old now. Calling himself “Devanampiya”, “Piyadasi”, or the “Beloved of the Gods” after his conversion into Buddhism, he commissioned these pillar edicts. In this pillar, four compartments of inscriptions preach his doctrines of pity, kindness to animals, prohibiting slaughters, even allowing three days of respite to prisoners under death sentence in the hope that they will spend these days in self examination and meditation.

Sirat-i-FirozShahi narrates:

..No bird can fly as high as its top..and arrows can not reach to its middle…O God! How could they paint it all over gold, (so beautifully) that it appears to the people like the golden morning!…

The Ashokan edicts on the Feroz Shah Kotla pillar were the first to be decoded by James Prinsep in 1837, thus finding the key to Brahmi script.

During the de-installation of the huge monolithic shining pillar at Tobra, first a massive bed of silk cotton was prepared onto which the pillar was carefully lowered and then it was covered with raw skins and reeds. Thousands of people were utilized in the process, it was skillfully transported by placing it on a 42 wheeled cart using numerous pulleys and revolving wheels, with 200 people pulling each rope attached to every wheel, and huge boats were used to take it across the Yamuna. Finally the Minara-e-Zarin, or the ‘Golden Column’, was erected at Ferozabad near the Jami Masjid on 30th Sept 1367. A covered corridor or a connecting bridge was built between the mosque and the pyramidal structure housing the pillar, perhaps to grant privacy to royal ladies.

Many learned Brahmin scholars were invited by the King to read and interpret the inscriptions, but none was able to do so.

( © A.S.I., New Delhi.

Illustrations from Sirat-i-Firozshahi. These images have been reproduced with the permission of ASI. It appears at Plate VI – a & b in their publication: MASI number 52, A Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi, published by Archaeological Survey of India, 1937, Reprint 1999. )

Later inscriptions on the pillar includes few from 1164, and few more in Devanagari script in 1524 corresponding to Ibrahim Lodi.

In 1398, when Timur of Khurasan attacked Delhi, he was impressed with these two pillars and said he had never seen such things in any other country.

The King’s court:

The Sultan’s 32 page memoir Futuhat-I Firoz Shahi and contemporary chronicler Afif’s Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi, provides few glimpses of nearly 4 decades of the third and last noteworthy Tughluq ruler from 1351 to 1388 .

It is said that when Muhammad bin Tughluq died in 1351, noblemen had to coax and convince his reluctant cousin Feroz Shah, the son of a Hindu princess, to accept the kingship who was otherwise planning to go to Mecca. Said to be most prosperous times of the Sultanate era, Firuz Shah’s 40 year rule is described by chronicler Afif as a period of abundance, cheap goods, flourishing villages, and happy citizens.

In spite of his philanthropic excesses like grants to officials and needy, and budgetary spending in restorations and infrastructure building; annual revenue of the court was at a staggering 6,75,00,000 tankas.

Three things are often used to describe Firoz Shah the best: his passions for good governance, building and hunting.

In the Sultan’s court, it was customary for visiting governors to present the king hordes of suitably ornamented and decorated slaves, along with fine horses and elephants. Firoz Shah made a new regulation to evaluate all such gifts and to credit back the amount to the provincial governor’s accounts. At one time, there were almost 1,80,000 slaves in the Kingdom who were utilized in all types of jobs: in the Army, as palace guards, trainee artisans, and also, slaves engaged in reading, and even in religious pilgrimage to Mecca etc. A separate administrative setup was established solely for the slaves.

However, orthodoxy and intolerance were his faults: idol-worshipping had been declared unlawful with severe punishments and even death, and he re-imposed Jizzya tax on Brahmins which he subsequently agreed to reduce to 10 tankas and 50 jittals per individual, after listening to the fasting Brahmins.

Firoz, the able administrator :

Few verses from his memoir best describe his administrative initiatives.

“Labor to earn for generous deeds a name, Nor seek for riches to extend thy fame.

Better one word of praise than stores of gold, Better one grateful prayer than wealth untold”

Known for his charity and care for people, he even paid money to a soldier so that he can bribe a clerk to get some certificate. He wrote off all debt agreements of citizens, banned undue extraction of taxes from people, land owners and Raiyats, enforced just market place practices, and even personally meeting all the unemployed people in the city and assigning them work.

“Better a people’s weal than treasures vast; Better an empty chest than hearts downcast”

He established diwan-i-khairat to help people with their daughters’ marriages, and set up free hospitals or shifa-khanas.

“Kings should mane their rule of life, To love the Great and Wise;

And when death ends this mortal strife, To dry their loved ones’ eyes. “

He ensured transfer of government position and jobs to the kin of those deceased and also he established a system of old-age care to royal employees.

“Would’st thou enjoy a lasting fame? Hide not the merits of an honored name!”

When he took over, only the ruling Sultan’s name was being read out during the religious address Khutbah in the mosques, and he changed the practice to include names of 12 Sultans to be in the reading list.

“Thanks for God’s mercies I will show, By causing man nor pain nor woe.”

He abolished all cruel penalties , e.g. amputation of hands and feet, ear and noses; Tearing out the eyes, pouring molten lead into the throat, Driving nails into the hands, feet, and bosom, sawing men in two, etc.

Firoz Shah, the prolific builder :

While the monuments of Slave Dynasty display ample delicate structural workmanship; and those from Lodi dynasty represent the fine fusion of Hindu-Islamic architectural imprints; and the poetic and lucid splendor in stone represent the Mughal style; in stark contrast; the Tughluq buildings seem to recoil into a severe studied gloom, dark and forbidding, and almost rude in their form.

Many new towns and cities including Hissar, Jaunpur, Firozpur; reservoirs (bunds), canals, madrasas, caravan-serais, free hospitals, palaces(kushk), hunting lodges, monasteries (khankahs) and royal establishments(kar-khanas) were built during Feroz Shah’s tenure. He also ensured restoration and repair of old tombs, domes, adding top two floors to Qutub Minar in marble when it was stuck down by lightning, opening up dried-up Hauz-i-shamsi & Hauz-I Alai, and restoration work of Jahanpanah. He built 120 monasteries and 1200 gardens in Delhi alone, and in each garden there were 7 varieties of white and black grapes, sold at one jittal per ser.

Two of his notable new cities are Hisar & Jaunpur.

The city of Hisar-e-Firoza was founded in 1354, mainly for travelers from Iraq and Khurasan. A walled fort with four gates with a palace, a tank and many underground quarters inside; it was set afire by Timur’s army in 1398. His pioneering work in diverting waters of Yamuna through a new canal to the new city was noteworthy, as the same canal was later extended by Mughal planner Ali Mardan Khan to water the streets of Chandni Chowk.

He constructed long water canals to cities through villages and farmlands, and made wastelands cultivable, thereafter asking villages to deposit 10% revenue as rent-deposit, that swelled the state’s coffers, as well as the farmers’ prosperity.

Jaunpur city was founded in 1359, and was named in the memory of Muhammad-bin-Tughluq, whose given name was Jauna Khan.

( For the L-shaped madrasa that he constructed in Hauz Khas, please see my previous post.

https://lighteddream.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/hauz-khas-the-14th-century-knowledge-city/)

Firoz Shah, the conqueror:

After defeating Mongols, Feroz Shah took up the now-customary military conquests to Bengal(including Orissa) and Sind (Thatta), twice each.

When he was on long military expeditions extending for years, his wazir Khan-i-Jahan was often entrusted to manage the administration in Delhi, whom the Sultan graciously described as “the real ruler”.

The Sultan’s military convoys were massive: the one to Bengal consisted of 70,000 cavalry, 470 war elephants, two outer tents, two reception tents, two sleeping tents and two tents for cooking and domestic work, 84 ass-loads of drums and trumpets, and numerous camels, asses, horses, and infantry, slave forces on male buffaloes followed by an axe-bearing force riding on Arab & Turk horses.

The first expedition of Firuz Shah was to Lalkhnauti, or Gauda in the Bengal where engaging for 11 months, his forces captured the city. At the end of the war, he declared one silver tanka for every severed Bengali head, and a staggeringly 1,80,000 slaughters took place.

After Bengal, he marched his army through Bihar to Orissa in 1361, where Bhanudeva III of Ganga Dynasty was in power, and conquered the impregnable stone fort of Barabati, a glorious epoch of the Imperial Ganga Dynasty, at the bifurcation of two rivers – the Mahanadi & the Kathjodi – and classified as a Jal Durga, or a Fortress surrounded by water. While the two rivers constituted the fort’s outer line of protection, a broad moat sheltered with crocodiles marked its inner boundary. Historian Afif writes, the Sultan was very impressed with the prosperity of people there, the abundance of fine animals, and their spacious houses having fruit gardens and walk-ways. Current excavations at the fort site reveal gargantuan remains of a fortified citadel, a pillared hall, a massive square edifice, and an elaborately carved gateway approachable by a low ramp. The large pillared structure was built over the ruins of a 12th century ancient Jagannath temple built by Anangabhima III, which was demolished by Firoz Shah Tughluq.

Sultan Firoz returned to Delhi with a huge booty after spending 2 years and 7 months in the military expedition to Bengal and Orissa, with 73 richly caparisoned captured elephants preceding him like a flock of sheep into Delhi, without any mahouts, so writes Afif. However, it is not clear as to although Sultan Feroz defeated the Orissan King, why he did not annex Orissa to his Sultanate; and King Bhanudeva III continued to rule till 1378.

While over-running Kangra in Himachal, he ordered thousands of books at the Jwalamukhi temple to be translated from Sanskrit to Persian.

Wishing to materialize the unfulfilled dream of his predecessor Muhammad bin Tughluq to conquer Thatta, in present day Pakistan, he set upon a military expedition there, but faced defeat and had to retreat to Gujarat where he was falsely led to Rann of Kutch salt deserts. Famine, separation from own men, salty desert and the necessity to walk on foot soon scattered his army, however, he regrouped and reinforced and marched once again to Thatta: this time he was successful, where his predecessor had died while trying to capture. After almost 2.5 years his army returned to Delhi.

Final Resting place:

Feroz Shah died in 1388 at the age of 90, and was buried in the exquisite square-shaped tomb with an unusual open courtyard overlooking the beautiful Hauz Khas, hoping for a peaceful afterlife in the academic air of the young students and the maulvis of the finest Muslim seminary and college that he had built in Tararabad, ‘the city of joy’.

He is often termed by the British, as ‘The Father of the Irrigation Department’ for his pioneering attempt in building canals and water supply routes in various cities that he built, apart from, of course, his restoration projects that may entitle him as the founding president of the Conservation Society of Delhi. A King who sought immortality through his buildings, he seemed to get the eloquent concurrence from religious quarters :

“He is not dead who leaves behind him on earth, Bridge and mosque, well and serai.”

“Who so buildeth for God a place of worship, Be it like the nest of Qata-bird; God buildeth for him a house in paradise.”

—————————————————————————–

Feroz Shah Kotla – the remains of the 14th century engine house of Tughluq Empire, with its thick fortification walls enclosing time-darkened rubble built remnants of Delhi’s first ever riverside city – is more popularly regarded as a revered Dargah rather than a historical monument; but who can be the saints invoked in this unusual one lying in utter ruins, via the medium of letter-writing?

“And we certainly created man out of clay from an altered black mud. And the Jinn, we created before, from scorching fire” ( The Quran 15:26 & 15:27)

Connecting generations and times beyond all possible human memories, Djinns are described to be associated with the Prophet himself from the very beginning:

“ In the age of Hazrat Nuh ( Noah),.. I told him that I was a part of the gathering of the killers of Habil bin Adam ( Abel, son of Adam). I desire God’s forgiveness. ..Hazrat Nuh said, God is forgiving and merciful..”

When God created the universe, man was born out of earth, Angels from light, and Djinns from fire. Made from vapor & smokeless fire, the Djinns roam around the world on eagle’s wings, and being mass-less, they can live anywhere. They were the first masters of the earth, mankind being the second. They are beings of free will – just like humans – and capable of both good and evil deeds. They do not belong to our universe, nor to the universe of the Angels, they live in an alternate dimension –a universe called Djinnestan in between the two.. However, for a Djinn to grant someone’s prayer, it must first love and care for the human, and accept him/her as its master. Djinns can take any form – humans, animals, fire, or any object, but only when they gain trust and get used to you, will they manifest in some form or maybe in dreams to the patient and respectful human.

The letter-writing custom to the otherworldly elusive Djinns is said to have some connection with Ibn Battuta’s report of citizens writing letters to Tughluq Sultans; even some resemblance with Firuz Shah’s seemingly strange effort to communicate with the spirit of his predecessor and cousin Muhammad-bin Tughluq through letters. In order to seek forgiveness from the kin of those tortured or killed by the previous Tughluq; Firoz Shah arranged signed ‘agreement-deed’ documents forgiving the late Sultan, in exchange for financial appeasement, and placed the letters in a trunk at the dead Sultan’s tomb for spiritual mercy.

In Feroz Shah Kotla, there always has been a trickle of people coming with their mercy petitions and letters to the Djinns, but after the 1977 emergency period when one fakir Laddoo Shah moved into the ruins, it started attracting hundreds of believers.

The letters to the Djinns are often written with clear legitimate handwriting, sometimes attached with photos, and with multiple photocopies deposited at various alcoves and niches: as if submitting an actual application to various departments of a modern government bureaucracy setup or office.

There are seven sub-terrain vaulted window-less rooms called the Sat-Dar. In these dark underground corridor, with the interplay of flickering candle lights and a darkness thick with incense smoke, the people themselves look ghostly and out-worldly as they visit chamber by chamber, one after another.

This story gets repeated every Thursday, when this 14th century medieval ruin becomes a place of worship for wish-granting Djinns.. monument entry ticket gets waived off, people from far and wide converge to stick their letters full of prayers and wishes – wafts of curling incense smoke and oil lamps… shining clothes and bangles.. clean mirrors to reflect the dual reality of man and Djinn.. scentless candles of white, black and blood-red color offered in the dark corridors and deep alcoves that are part-illuminated .. all designed to invoke and communicate with an alternate world of timeless Djinns.

‘Yeh Insaaf ki Jagah hai’, a Place of Justice: and that is what it turns into, after night draws its cloak over the ruins every Thursday night, and the last of the devotee has left the place. It is said there is a ‘Sarkar’ or Government of the Djinns with various Ministries and Departments, just like ours; and they converge here every Thursday to read all the photocopied letters and grievances left behind to decide and approve the petitions.

Of all the Djinns, the name of ‘Nanhe Miyan’ or the ‘Little Mister’ stands out over the ages. In a city and world where human saints are rooted to their graves, the Djinn saints of Feroz Shah Kotla represent mobility: who can travel between India and Pakistan every 10 minutes.

The story goes that the 18th century mystic Shah Waliullah was once praying at the Kotla mosque, and on seeing a snake approaching him, he killed it with a stick. The same night, he was carried away to the Djinn’s government in the Kotla ruins, and was charged with murder of the Djinn King’s son who had taken the form of a snake: however he was forgiven for his ignorance and due to his association in that assembly with an old Djinn – a companion of the Prophet – he overcame thousands of years of his destined life-circle, and rose to become a great mystic scholar.

————————————————————————————-

Thanks and References:

Thanks to Kanika Singh of Delhi Heritage Walks ( http://www.delhiheritagewalks.com ) for leading the exploration of the site of Kotla Feroz Shah, along with Moby Sara Zachariah. Thanks to the office of Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi for their kind support.

- “The Bowl that Sinks and Tells Time”, in “The Archaic & the Exotic” by Prof S.R. Sarma, Dusseldorf, Germany ( www.srsarma.in). My sincere thanks to Prof Sarma for patiently responding to my emails, referring me to extremely useful reference sources on Feroz Shah, as well as clarifying my understanding of the ‘Tas-i-ghariyal’, the exotic water clock, during Feroz Shah’s times.

- “Jinnealogy: Everyday life and Islamic theology in post-Partition Delhi”; by Prof Anand Vivek Taneja, Vanderbilt University, USA. My sincere thanks to Prof Taneja for providing me a copy of his published article that helped me immensely with Jinnealogy & its association with Feroz Shah Kotla.

- A Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; by J.A. Page & Mohammad Hamid Kuraishi, (1937, Reprint 1999), Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.

- The History of India, as told by its own historians (Vol III) by Sir H.M. Elliot & John Dowson

- The Seven Cities of Delhi; by Gordon Hearn.

- Delhi : Its Monuments and History, by Percival Spear

- Vikramjit Singh Rooprai’s blogpost “Tilangani’s 7 Wonders of Delhi” : https://vikramjits.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/tilanganis-7-wonders-of-delhi/

- TOI Article: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/On-Thursdays-Kotla-turns-Aladdins-lamp/articleshow/12214806.cms

- Architecture Ground Plan of Firoz Shah Kotla: http://www.archinomy.com/case-studies/1914/site-visit-to-feroz-shah-kotla

- Djinn Summoning, by Dalida Carta

- Delhi & its Neighborhood, by Y D Sharma

- Painting by Thomas Daniell, “Oriental Scenery”, 1795; source : British Library http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/other/019xzz000004321u00007000.html

- My sincere thanks to all the helpful experts at ASI, Bhubaneswar for presenting me their book “Impregnable Fort Barabati; by Dr Dillip Kumar Khamari, Archaeological Survey of India” to link the excavated Fort with Firoz Shah’s conquest of Orissa.

- The History of the Imperial Gangas of Orissa, by Bishnu Prasad Panda